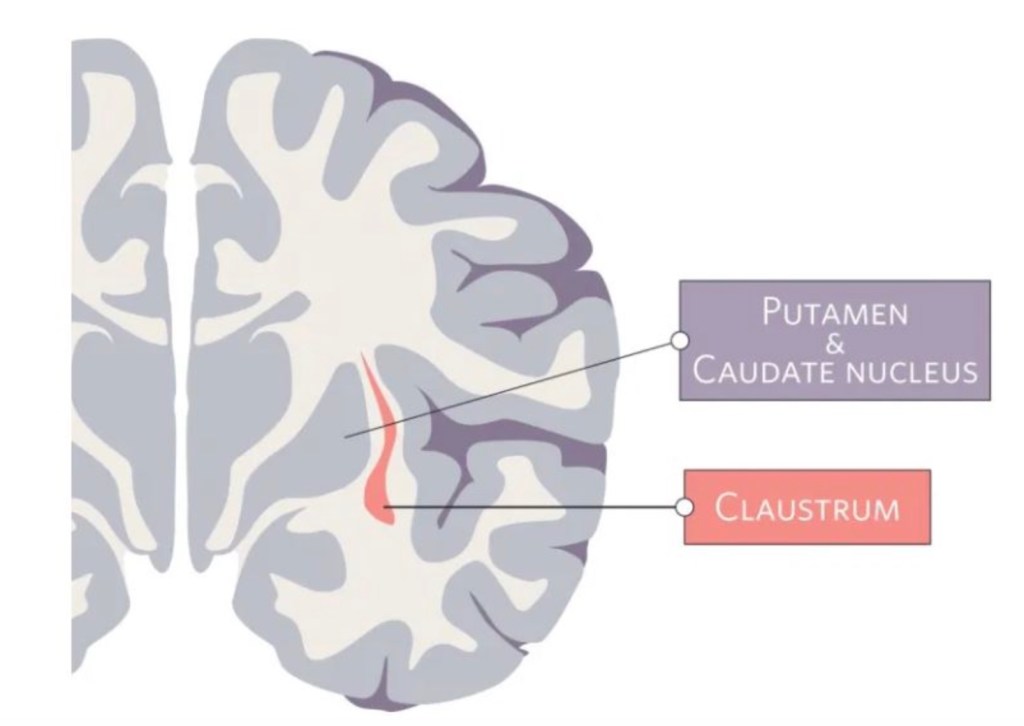

The claustrum is a region in the brain formed by a thin sheet of neurons sandwiched between the insula and striatum. This region holds the notable position of being the most densely connected part of the brain by size. Most of these connections are to or from areas across the neocortex – the part of the brain involved in sensory processing and executive function. While the exact function of the claustrum remains unknown, the claustrum’s privileged position in the brain has captured the interest and imagination of scientists for many years.

Not surprisingly, given the claustrum’s dense projections to frontal lobes and sensory cortices, one emerging hypothesis is that the claustrum plays a role in sensory processing. In a recent study from our lab, we wanted to investigate how claustrum projections to one frontal brain region, the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), influence pain.

The first question we asked was whether a painful stimuli could change the activity of claustrum neurons that project specifically to the ACC. We specifically labelled these neurons by injecting a fluorescent dye (CTB-647) into the ACC of mice. After a couple weeks, the dye is taken up by axons in the ACC and transported back to the cell bodies in the claustrum (sort of like the old ‘celery in dye experiment’. If you put the cut end of a celery in a coloured liquid, overtime the leaves on the other end turn colour too). This strategy allows us to visualize the subpopulation of claustrum neurons that project to the ACC. We could then apply different sensory stimuli to our experimental animals and use different techniques to visualize whether these neurons are active or not (cFOS labelling and in vivo calcium fiber photometry, for those interested). What we learned is threefold: first, is that pain, but not other tactile stimuli, evoked a response from the claustrum. Second, we learned that the highest activity occurred after the painful stimuli was removed, suggesting the claustrum may be playing a role in pain resolution or pain learning as well. Finally, we learned if an animal had a history of pain (for example, experienced a mild inflammation of the hind paw over the past few weeks), pain stimuli was no longer able to evoke any activity in the claustrum. Overall, this data suggests that the claustrum is involved in normal pain processing, and this pathway is lost in chronic pain.

The next question we asked was whether inhibiting the claustrum neurons that project to the ACC influenced pain behaviours. We used a viral-directed lesion approach that essentially allows us to turn off precise populations of neurons in awake, behaving animals. We found that when we inhibited claustrum neurons projecting to the ACC, animals became hypersensitive to sensory stimuli. This is reminiscent of our chronic pain model that was characterized by loss of function of the claustrum and pain hypersensitivity. Finally, despite the pain hypersensitivity, we found that inhibition of the claustrum pathway interfered with the ability to form a pain memory. This data suggests that the claustrum pathway is required for establishing normal sensory sensitivity and pain learning. Loss of this pathway results in pain hypersensitivity, yet impairs pain memories.

The last question we asked was whether restoring claustrum activity in animals who were experiencing chronic pain was sufficient at restoring normal pain behaviours. When using a chemogenetic approach to selectively activate these neurons, we found that we could entirely reverse the pain hypersensitivity of these animals. The level of analgesia produced by activating this pathway was like what we see with a very high dose of an opioid, such as morphine.

Taken together, these data reveal that the claustrum plays an important role in pain processing and integration. It suggests that changes in activity in the claustrum may contribute to the transition of chronic pain, and targeting the activity of the claustrum may prove to be an effective therapy for chronic pain in the future.

This project was recently published in the journal Current Biology. It was led by our talented PhD student Christian Faig, and was supported by a federal grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research awarded to Anna Taylor and Jesse Jackson.

You can read the full paper here.